|

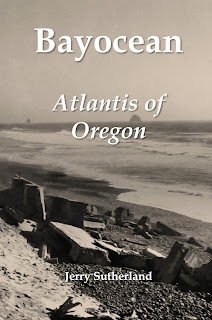

The house last owned by Harry Roberts, photographed by the

Corps of Engineers in February 1940, not long before it fell. |

After first hearing about Bayocean eight years ago, I set out to locate the schoolhouse and six cabins (counting the Pagodas as two) moved to the mainland before the south end of the spit was blown out by a storm surge in November 1952, a disaster from which the resort town never recovered. I had just located the last of them when Grant McComie called in June 2015 to ask for assistance regarding a program on Bayocean. I then thought it would be interesting to know where the buildings were located on the spit. That led to an obsession with finding every residence ever built on Bayocean, and to learning as much as I could about the homeowners who lost them. It took me another seven and a half years to achieve that goal.

If Bayocean Park had been platted in the 1970s, it would have been much easier to locate buildings because property owners would have been required to purchased permits and get an inspector's approval before occupying their homes, resulting in a detailed chronological record readily accessible at the Tillamook County Courthouse. But while the resort town of Bayocean existed, none of that was the case. Homebuilding was a kind of free-for-all. So, I was forced to look for names in newspaper articles, then search deed indexes at the county clerk's office, track ownership back and forth, and go back to look for the other names in newspapers.

Most large metropolitan newspapers like the Oregonian were digitized, so I was able to search them online, but that was true of very few Tillamook County newspapers. So, I read every original edition or microfilmed copy looking for any mention of Bayocean. Information I was excited to find one day often conflicted with information found elsewhere later. Personal memoirs, government reports, and other archival records helped me parse it all out and fill in gaps. I ran into many dead ends along the way, but most of the remaining pieces of my self-induced Bayocean puzzle fell into place when Denise Vandercouvering, Tillamook County Assessor worked out a way for me to look through historical assessment rolls stored in the courthouse basement after I learned they were organized chronologically by subdivision - just what I needed.

In Bayocean: Atlantis of Oregon, hopefully published in the next couple of months, I will tell the story of homeowners I was able to find, so readers can get a sense of what they experienced. And I mention at least the first and last owners of each of the fifty-nine houses built and lost on the spit. Some were magnificent, some were shacks or converted garages, but they were all considered home by someone.

My tally does not include houses on the mainland - one of which was destroyed, others moved, some more than once - because my book is about the spit, which I consider everything north of South Gap (Shell Street and 2nd Avenue) because it was the southern limit of the November 1952 blowout. I counted the Pagodas as two houses because one was built later than the other on the spit, lived in by different individuals, and referred to as such by neighbors. Others might choose criteria that result in a different tally.

To help myself and readers keep track of the fifty-nine residences, I built a spreadsheet listing each one, their demise, lot numbers, and the last names of each owner. Unfortunately, it was too large to include as an appendix in my book, but you can view and/or download it here. Locating each home will require you to view and/or download the Bayocean Park plat map, which I could not fit on two pages pages of my book and provide sufficient detail.

%20&%20Post%20Office.jpg)

%20postmaster..jpg)

,%20no%20pricing.jpg)